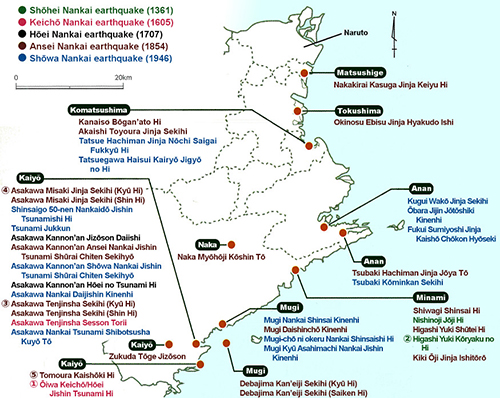

Kaiyō Town, Mugi Town, Minami Town, Anan City, Naka Town, Komatsujima City, Tokushima City, Matsushige Town, Tokushima Prefecture

Muromachi–Shōwa periods (fourteenth–twentieth centuries)

Ōiwa Keichō/Hōei earthquake tsunami memorial ①

Inscriptions for earthquakes of two different periods are carved on a boulder (ōiwa). The contents of the one on the left relate to the Keichō Nankai earthquake, and together with the characters for the nenbutsu (“Namu Amida Butsu,” the chanted name of Amida Buddha), it records that more than 100 persons were victims of the tsunami. The one on the right is a memorial for the Hōei Nankai earthquake, and is inscribed with a statement that “although tsunamis about 3 m high came three times, there were no victims.” The small shrine to the left of the inscriptions houses a statue of Jizō (a bodhisattva). The boulder is 3 m in height.

Distribution of memorials

Based on the 2016 survey, there were 39 memorials identified. The majority of these were set up on the precincts of Shinto shrines. They ranged from those related in the distant past to the Shōhei Nankai earthquake of 1361, to the stone monument of recent years at the Kugui Wakō shrine in Tachibana, Anan city, in which along with the 1946 Shōwa Nankai earthquake, the height of the tsunami from the Great Chilean earthquake of 1960 is inscribed. Adapted from Hakkutsu sareta Nihon rettō 2017 [Excavations in the Japanese Archipelago, 2017] (Bunkachō [Agency for Cultural Affairs], ed., Kyodo News, 2017).

Higashi Yuki Kōryaku memorial ②

Erected in the second year of the Kōryaku era (1380), it is said to be the oldest earthquake and tsunami memorial in Japan. It is related to have been erected for the repose of victims of the Shōhei Nankai earthquake, which is recorded in the Taiheiki chronicle. Height: 196 cm.

Asakawa Tenjin shrine stone monument ③

There are two memorials, the older one (photo) erected in 1867, and a newer one set up as a replacement due to deterioration of the older item. In the inscription, in addition to the extent of damage from the Ansei Nankai earthquake (1854), the periodicity of the earthquakes is also noted: “[tsunamis] came twice, in the Eishō [1512] and Keichō eras [1605] . . . The interval between the Keichō and Hōei earthquakes was around 100 years, but this time the earthquake came in the 148th year.” Height: 171 cm.

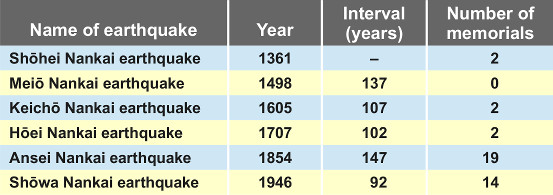

Numbers of memorials seen by period

Nankai earthquakes occur with a periodicity of 100–150 years. Adapted from Hakkutsu sareta Nihon rettō 2017 [Excavations in the Japanese Archipelago, 2017] (Bunkachō [Agency for Cultural Affairs], ed., Kyodo News, 2017).

Asakawa Misaki shrine stone monument ④

A memorial for the tsunami of the Ansei Nankai earthquake, erected in 1901. After recording in detail the conditions of damage from the earthquake, it writes down these lessons: “As many deaths resulted from boat rides in Osaka and other places, one should never think of trying to escape by boat. . . When this type of earthquake and tsunami occur again more than 100 years from now, as there will invariably be forewarnings, it is essential to set up temporary structures on hilltops as preparation for residence.” Height: 132 cm.

Tomoura tsunami memorial ⑤

This is a record of the conditions of the Ansei Nankai earthquake and tsunami that began on 23 November 1854 (eleventh month, fourth day, seventh year of the Kaei era in the traditional calendar). It relates that as great earthquakes “have since ancient times come without fail around every 100 years, the infantryman Okazawa Yukimasa felt great anxiety, and consulting with the mayor Takahashi Hosuke, sought to inscribe an account in stone to inform posterity.” In consideration of the gravity of the situation, the then district supervisor Takagi Shinzō (Munenori) decided to erect a memorial. The inscription is dated to the autumn of 1855, but the actual erection of the memorial was 72 years later, in 1927. Height: 205 cm.

Valuable memorials relating lessons from the Nankai earthquakes

What 39 memorials within the prefecture have handed down

Tokushima prefecture has been inflicted with severe damage by Nankai earthquakes many times in the past. Conditions of damage have been confirmed from historical documents and through excavation. Beginning with the Higashi Yuki Kōryaku memorial erected in 1380, said to be the oldest tsunami memorial in Japan, many monuments and stone structures commemorating Nankai earthquakes or tsunamis, or as memorials to their victims, have survived and just those that have been confirmed number 39 items. In the 2016 fiscal year, a comprehensive survey of these memorials was conducted, and investigations have proceeded of their dates of erection and the contents of their inscriptions, their forms and stone materials, states of deterioration, and so forth.

The memorials are distributed centering on the southern portion of the prefecture, and in particular there are 16 items located in the town of Kaiyō which borders on Kōchi prefecture. Looking at the numbers of memorials in terms of the dates of the Nankai earthquakes, those related to the Ansei Nankai earthquake of 1854 are most frequent, followed by the 1946 Shōwa Nankai earthquake. Regarding the contents of the inscriptions, records of the earthquake conditions are the most numerous across every era, and items are seen with lessons attached or prayers for the repose of the victims. All of them may be called valuable sources of information that should be drawn upon for future disaster preparedness.

Also, when conducting the survey many local residents provided cooperation, and on those occasions expressed a desire for explanatory signboards, or voiced concerns about the deterioration of the memorials. In order to pass on the lessons of our predecessors to posterity, and prepare to face unprecedented natural disasters, the task of spreading information about the memorials, and devising methods for their utilization and measures for their protection are issues for the future. (Ōhashi Yasunobu)