Iwami Ginzan Silver Mine:

World Heritage Site Iwami Ginzan Silver Mine and Its Cultural Landscape

Noted on Maps from Europe

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries of the Age of Discovery, people in Europe knew that Japan, which lay on the eastern side of East Asia, was a “kingdom of silver,” a “land of silver mines.” Maps made at the time had the words “silver mine” written on the Japanese archipelago. The oldest such example is a map drawn by Bartholomeu Velho in 1561. Japan is drawn divided into several blocks with names reminiscent of political regions of the day, such as “Bandō,” “Miyako,” and “Yamaguchi.” Near the center is “minas da prata” (silver mine); this is thought to be Iwami Ginzan. To the Europeans, to speak of silver mines probably meant to speak about Iwami.

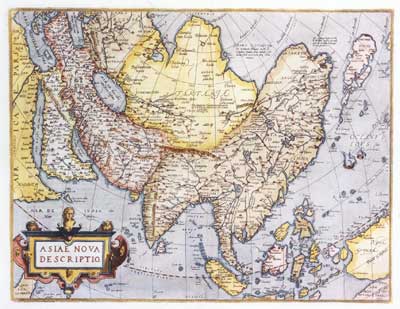

Shown here is the map of Asia made nine years later by Abraham Ortelius, which closely followed Velho’s map. The “BANDUMIA” in eastern Japan and “COO” in the center result from mixing up “Bandō” and “Miyako.” Above “COO,” towards the Japan Sea is written “minas da prata.”

(Toya Yoshio)

Ortelius map of Asia First published in 1570. It is 37.0 cm in height by 48.7 cm wide.

Teixeira map First published: 1595. Height: 43.3 cm; width: 55.3. cm.

A map of Japan made in Antwerp, Belgium. The Latin gloss Argenti fodinae (silver mine) is inscribed near the place name “Hiwami.” As this is the only silver mine noted on the map, it is seen to be the representative example for Japan.

Iwami Ginzan Silver Mine Site as World Heritage

Reasons for registration on the World Heritage list

The Iwami Ginzan site gained recognition as World Heritage for the following reasons.

First, it provided the chance for Japan to appear front and center on the world stage through its active production of silver from the sixteenth to the early seventeenth centuries.

In the first half of the sixteenth century, Iwami’s silver production increased dramatically when the cupellation method of silver refining was introduced there.

Subsequently, this method was transmitted to mines in Sado (Niigata prefecture) and Ikuno (Hyōgo) and elsewhere, propelling Japan to become one of the top silver producing countries in the world at the start of the seventeenth century.

At the time Europe and Japan needed large amounts of silver, in order to import silk and porcelain from China, which used silver for its domestic currency. Because of the Japanese silver rush that began at Iwami Ginzan, silver from Japan started flowing into this trade cycle in large volumes.

In order to boost profits through its trade with China, Europe engaged actively in commerce with Japan to procure low-priced silver. As part of this European goods such as guns flowed in, closely followed by the arrival of Christian missionaries. The history of the Age of Discovery cannot be told without including Iwami Ginzan.

There are indications that even a portion of the chōgin coins, used by daimyo of the Sengoku period for their war treasuries and bounties for military service, were in circulation abroad along with European silver coins.

The second reason is because the production methods of the time have been rendered clear. From mining to refining, they are vividly preserved in the work places and tools, in the many archaeological features and artifacts. More than 600 remains of pits and mining shafts survive, and nearby are more than 1,000 level areas that are the sites of cemeteries and temples, and of silver refining work and daily living, from which in addition to silver production equipment, such as iron pans for silver refining, and cupelled silver produced by the refining, items which at the time were only used in cities are recovered, such as imported glazed ceramics and ornamental glass hairpins.

The third reason is that the entire outlines of the process from the production to the transporting of silver are preserved as a heritage site together with the natural setting. The Iwami Ginzan site, centering on the silver mine, is comprised of roads, ports, and mountain fortress remains. As worthy of further note, the mining town which at its height held a population of tens of thousands of people, and the port towns which supported it, still serve the region’s residents as arenas of daily life.

In addition, the mountain forest, which supplied the huge amounts of wood fuel needed for silver refining, has been maintained by a unique system of forest resource management, based on prohibitions on felling along with the planting of trees in planned fashion, so that a richly green landscape has been preserved which is not seen in silver mine sites of foreign countries.

The path to registration

In 1969, its historic value was recognized and Iwami Ginzan became the first silver mine site to be nationally designated as a Historic Site. Also, the important role of Japanese silver in world history was pointed out early on among researchers of mining.

In the midst of these developments, a plan to register Iwami Ginzan as a World Heirtage site was launched in 1995. The following year a comprehensive investigation was initiated by Shimane prefecture and the local municipality of Ōda (consolidated from the former city of Ōda, and the former towns of Nima and Yunotsu), centering on excavation and including the study of science, documents, and carved stone objects, and in 2001 the site was included in Japan’s Tentative List for World Heritage. Then in 2007, twelve years after the start of the plan, the site was inscribed on the World Heritage list.

Present-day cities in Japan have mostly developed from a base as a castle town centered on a fortress of the early modern age, and may be said to sit atop “living archaeological remains” that are easy to comprehend. But what of the case of the mining town centered on a mine of the medieval or early modern periods, which in former times were likewise alive with gatherings of many people? Are not most of those places simply archaeological sites where the mining town survives as a place name only, along with the mine remains?

It is hoped that through the registration of the Iwami Ginzan site on the World Heritage list, the existence of such dormant mine remains that were once linked to the outside world will become known to many more people.

(Tsubaki Shinji)The Cultural Landscape of the Iwami Ginzan Site

The landscape of a mining site

Just what kind of site is the Iwami Ginzan site? It is a mining site that produced silver across roughly four hundred years from the sixteenth century. But it is not simply the mines and mining town centered on silver production, but includes as well the harbors and port towns used for loading and shipping silver ore and chōgin coins, and for landing provisions, plus the roads linking these together, as well as the remains of the fortress for protecting the mines, and collectively these are all called the “Iwami Ginzan Silver Mine Site.” The area is approximately 440 hectares, equivalent to eighty times the size of the Tokyo Dome and among the largest designated historic sites in Japan.

At the center of production was Mt. Sennoyama, where the silver sleeps. Near the top of this mountain and on its ridges and in its valleys, a mining city was built, and the manner in which the work from mining through refining was conducted within the mountain interior known as Ginzan Sakunouchi (literally, “inside the silver mine fences”) has been clarified through archaeological excavation. Near the mountaintop, during investigations of the Ishigane area, which was also called Ishigane Sengen (a reference to its many buildings), a road from the sixteenth to the seventeenth centuries, and the remains of buildings that were lined up along both sides have been discovered. Within the buildings furnaces were constructed for smelting and refining, and as tools for mining and the smelting and refining processes have also been recovered, silver production is thought to have been conducted. In addition to these materials, articles from daily life such as tableware and cooking utensils have been found, so it is clear the workers were also living in the same structures. From one of these buildings an iron pan used in the cupellation process has been discovered.

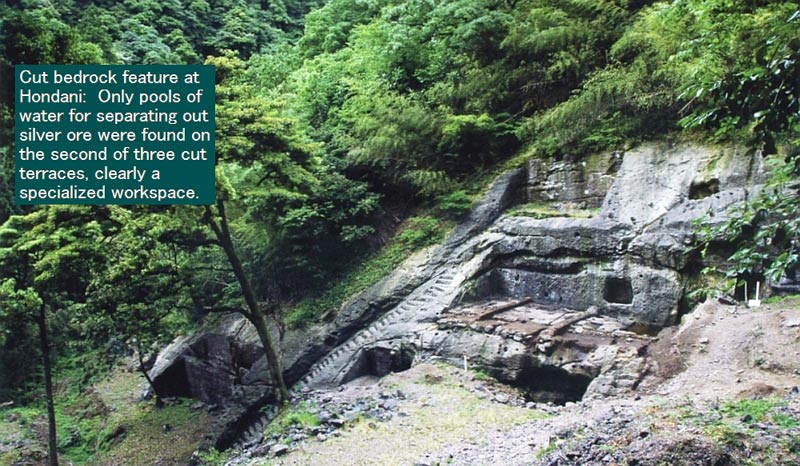

Investigations in the Hondani area, on the southeastern side of Ishigane, uncovered a feature made by cutting into the bedrock to fashion a three-terraced feature, the second terrace having six pools for water, within which there was sediment produced when silver ore was separated out, showing this was a specialized workspace. In the vicinity the remains of a building were found, constructed on foundation stones and supplied with furnaces and water storage facilities, where a range of processes in smelting and refining are inferred to have been conducted, along with a silver-lead alloy called kien which is produced during the refining process.

Numerous buildings with furnaces for smelting and refining have been found on level areas that were made by cutting into the ground surface and piling up earth. Small-scale smelting and refining was carried out within each structure, and it is clear that such small-scale processing, conducted in great numbers as domestic handicraft, supported the production of large amounts of silver. More than 100 furnace remains of this type have been found in excavations thus far.

Towns with a continuing landscape

The mountaintop town now lies buried in the soil, but others survive even today on the mountain slopes. The town of Ōmori, which stretches in narrow fashion over approximately three kilometers, grew as a mining town in conjunction with the development of the silver mines. Discovered in the first half of the sixteenth century, Iwami Ginzan thereafter became the prize of struggles among Sengoku daimyo, but with the Edo period the silver mines came under direct control of the bakufu and a magistrate’s office was placed at Ōmori, with the town becoming the base for its rule. Edo period townscapes are well preserved there, and it has been selected as an “Important Preservation District for Groups of Important Historic Buildings.” From investigations in the vicinity of the magistrate’s office, in addition to the many lacquer bowls and geta, etc., that were unearthed, boundary ditches and building foundation stones have also been found, and the outlines of a town of the Sengoku period have come to light.

About 100 m north from this point, in the Miyanomae area at the edge of town, as many as 24 furnaces for processing metal were found in a single structure, despite being separated by three kilometers from Sennoyama, and this is thought to be a workshop for heightening the grade of refined silver.

Although excavations have yielded tremendous results such as these, the investigated area of about 5,000 m2 is but one percent of the site taken as a whole. These results are due to rigorous selection of locations to excavate, so that effective investigations can be conducted with just a limited area.

Even though the mines are gone, people live yet today in mining and port towns. As “continuing landscapes,” these towns help constitute the unique cultural landscape of Iwami Ginzan.

(Nagamine Yasunori, Shinkawa Takashi)

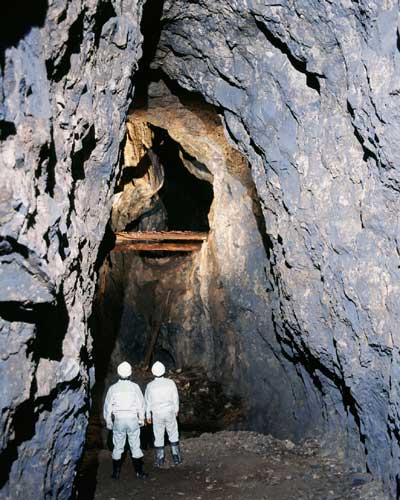

Ōkubo shaft There are so many shafts in its interior that Mt. Sennoyama can literally be called a “silver hive.” The shaft pictured here is of the greatest class in size, and further in lies a cavity even more enormous (now open to the public). |

Iwami Ginzan seen from the air above the Japan Sea (from the northwest) The fishing port at center foreground is Tomogaura, where silver ore was loaded and shipped at the start of the mine’s development. Going east over a road of seven kilometers from here one reaches the silver mine (at the photo’s center). |

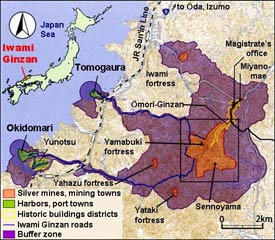

Extent of the Iwami Ginzan Silver Mine site and the Ginzan Sakunouchi area The Iwami Ginzan Silver Mine site is comprised of fourteen heritage components including the silver mine site and mining towns, roads, ports and port towns, and fortress remains. The central silver mine site, the Sakunouchi area, was strictly fenced off at the start of the Edo period, with guardhouses at the entrances and exits. Artifacts and features are well preserved here, beginning with those related to the mining town and silver production, and including others connected with daily livelihood, the circulation of goods, and religious faith.

Okidomari The inlet extending deeply inland is a good natural harbor, and was used for shipping silver and various other goods to ports on the Japan Sea such as Hakata. At the shoreline survive many mooring facilities called hanaguri iwa for securing boats. |

Yamabuki fortress site These are the remains of a mountain fortress adjacent to the mine on the north. The difference in elevation from the base of the slope is 240 m. In the Sengoku period struggles for the silver mine were made repeatedly by the Ōuchi, Amago, and Mōri forces. |

Road and building remains in the Ishigane area In the Ishigane area near the top of Mt. Sennoyama was a town that could be called a mining city. On both sides of the two-meter wide road visible in the foreground of the photo stood rows of buildings, and the existence of neatly sectioned town houses is clear. |

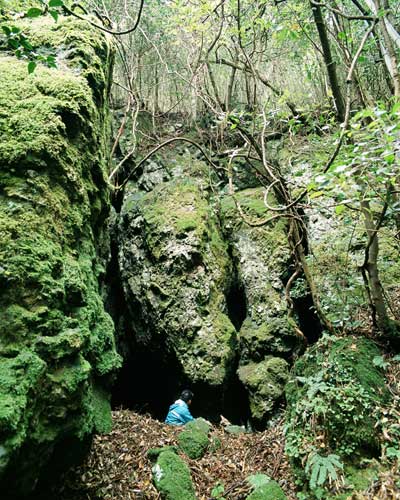

Traces at Mt. Sennoyama of digging to follow a vein The three deep trenches, extending vertically, and the shaft are the traces of digging along the course of a silver vein. In this method the shaft followed the vein by being dug at an angle downward from the ground surface. |

| |

Building detected in the Miyanomae area This building, which had as many as 24 refining furnaces (such as the one indicated by the arrow), is inferred to have been where the final stage of silver refining was carried out. |

A refining furnace in the Miyanomae area building Silver was refined in a small-scale furnace made by digging at hole 40-60 cm into the ground surface. It is seen here that four furnaces were built one after another in a row in the central area of the photo. |

Iron pan Ishigane Fujita area, late sixteenth century. Diameter: approx. 23 cm.; height: approx. 14 cm. Recovered from a workshop floor. A spout and three legs are attached; the item survives nearly in its entirety. Bone ash was detected through scientific analysis of the dirt on the inside, confirming its use for cupellation. |

Scale weights First half, seventeenth century. (Item at right) Length: 2.2 cm. (Item at center) Length: 2.3 cm. (Item at left) Length: 3.1 cm. The dumbbell-shaped item at right, whose outline is seen on maps in Japan today as the symbol for a bank, was used with a two-pan scale. The rectangular items with rings at the top were attached singly to beams for ease of carry. In assaying the quality of refined metal the two-pan scale was used for accurate measurement. |

Tuyere Mid-seventeenth century. Length: 14.8 cm. A tuyere is the nozzle attached to the tip of a bellows. Made of clay. Tuyeres are normally round, but those from Iwami and Sado are known for having a square outline. The diameter of the hole is approximately 2 cm, which was the best size for controlling the temperature. |

Chisel (left), pickaxe First half, seventeenth century. (Chisel) Length: 8.9 cm. (Pickaxe) Length: 11.6 cm. The chisel and pickaxe were used in digging silver ore. The chisel was commonly called tetsuko (iron child), and at Iwami Ginzan 10,000 of these items were used up annually. The name for pickaxe (tsuruhashi) was written with the characters for “crane” (bird) and “bridge,” and was used for digging through softer portions. |

Bizen stoneware First half, seventeenth century. (Item 1, Karatsu Tenmoku bowl) Height: 7.0 cm; rim diameter: 10.6 cm. (Item 2, Chosen Karatsu sake bottle) Height: 21.0 cm (inferred); base diameter: 7.6 cm. (Item 3, E-Karatsu vase [mizusashi]) Height: 12.8 cm; rim diameter: 11.2 cm. (Item 4, E-Karatsu dish [mukōzuke]) Height: 5.1 cm; rim diameter: 13.5 cm. (Item 5, speckled Karatsu sake cup) Height: 4.1 cm; rim diameter: 6.5 cm. Tenmoku bowls, mizusashi, and mukōzuke vessels show that while Iwami was a silver mine, the cult of the tea ceremony had been adopted there. This shape of sake bottle is known as one that was pioneered at Karatsu. The sake cup is a type of straw-ash glazed item known as gangakukei, and is said to have been used not exclusively for drinking sake but also as a vessel for condiments. | |

|

Huanan sancai (plus others) Late sixteenth-early seventeenth centuries. (Item 1, jade-glazed plate rim) Diameter: 5.4 cm (inferred). (Item 2, Huanan sancai dish) Diameter: 26.4 cm (inferred). (Item 3, jade-glazed plate bottom) Diameter: 6.1 cm (inferred). Huanan sancai is pottery made in China’s Huanan district, noted for fitted bowls and plates, pitchers, and so forth. Prized as luxury items, nearly all finds come from large metropolitan areas or trade cities such as Miyako (Kyoto), Sakai, Bungo Funai (modern Ōita). At Iwami Ginzan, it was recovered from the mining city of Ishigane. |

|

Blue and white porcelain Late sixteenth-early seventeenth centuries. (Item 1) Diameter: 12.9 cm (Item 2) Diameter: 4.8 cm (Item 3) Diameter: 13.6 cm Imported porcelain made in Ming China. Blue and white porcelain is called seika (blue flower). Such imported porcelain is found in quantity at Iwami Ginzan. This type of item is recovered from all over Japan, and was traded in silver. |

Photos courtesy of Ota municipal board of education.