Takashima

Kōzaki:

The keel of a ship from the Mongol invasions finally reveals its form

on the seabed. After a long and difficult underwater investigation,

the finds are collectively designated a Historic Site.

A ship from the Mongol invasion, in situ To the left is the keel, and on the right the outer planking of the ship’s bottom can be seen. The excavation site lies in waters 200 m distant from the Takashima shoreline, on the seabed at a depth of about 23 m. Prior to the excavation, a topographic map of the seabed was made using sonar sounding equipment for the entire area of Imari bay, data were gathered and analyzed on seabed strata, and a distribution map made of items giving responses thought to be artifacts from the second Mongol invasion, submerged beneath the sea floor. For the 2011 investigation, one such item was selected, an investigation area of approximately 15 m east-west by 10 m north-south was laid out, and an underwater excavation conducted. Adapted from Hakkutsu

sareta Nihon rettō 2012

[Excavations in the Japanese Archipelago, 2012] (Bunkachō

[Agency for Cultural Affairs], ed., Asahi Shimbun Publications,

2012).

|

An anchor (No. 4) pulled up from the bottom This wooden anchor recovered in the 1994 investigation had an anchor stone attached to each side. Extant length: 2 m 10 cm.

Mortar along the sides of the keel A square timber roughly 50 cm on a side was used for the keel, and mortar was applied to the portions on both sides. The external planks were 15–25 cm in width, about 10 cm thick, with lengths ranging from 1 to nearly 6 m, and they line up in orderly fashion on both sides of the keel over an area from 2 to 5 m wide. |

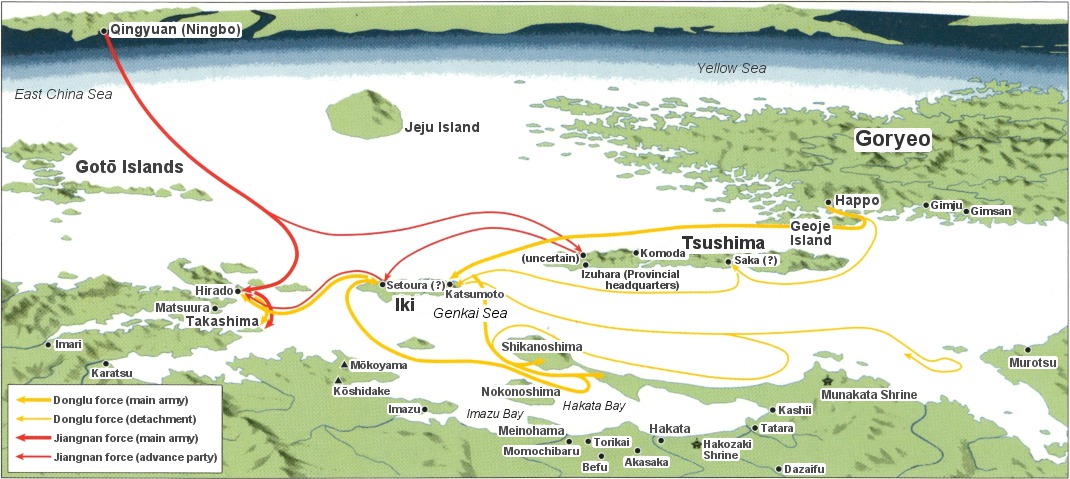

Routes of the second Mongol invasion Adapted from Hakkutsu

sareta Nihon rettō 2012

[Excavations in the Japanese Archipelago, 2012] (Bunkachō

[Agency for Cultural Affairs], ed., Asahi Shimbun Publications,

2012), originally produced by Tube Graphics Co., Ltd., and taken with

some modification from Nihon

no rekishi [Japanese

history], vol. 9 (enlarged and revised edition, Asahi Shimbun

Publications, 2002).

| |

Takashima Kōzaki Historic Site, Matsuura City, Nagasaki Prefecture

Artifacts related to the Mongol invasions are recovered

The Chinese Yuan dynasty emperor Kublai Khan twice attempted to invade Japan, in 1274 and 1281. These are known in Japan as the Mongol invasions. It is related that in the second invasion, many of the ships that took refuge from a typhoon at Imari bay in northern Kyushu met with disaster. In investigations up to the present, numerous artifacts related to the event have been recovered particularly from the waters off the southern shore of Takashima, an island located at the mouth of the bay.

A gathering at Imari Bay during a typhoon

Descriptions of the Mongol invasions survive in documents of both Japan and the Yuan dynasty. According to the History of Yuan (Ch. Yuan shi), having destroyed the Southern Song dynasty and unifying China in 1279, the Mongols drew up two forces in 1281, the eastern Donglu and the southern Jiangnan armies, planning the conquest of Japan. The eastern Donglu force sailed from Happo in Goryeo (now Masan in South Gyeongsang province, South Korea) on May 22, passing through Tsushima and Ikki islands and attacking Hakata, but retreated to Ikki after meeting fierce resistance from the Japanese. Meanwhile, the southern Jiangnan force sailed sometime around the beginning of July from Qingyuan (modern Ningbo, Zhejiang province, People’s Republic of China), at the mouth of the Yangtze river, headed for the island of Hirado.

In July the two armies joined at Hirado, and drew up a battle formation in the vicinity of Takashima in order to invade Hakata bay. It was a great armed force with as many as 4,400 ships and a total of 140,000 men. Already captured by the Mongol force, looking over Imari bay with its gentle waves, the island of Hirado seems to have been chosen as the site for mooring this great fleet. But a typhoon arose on August 15 and raged fiercely for two days, and the Mongol army was dealt a devastating blow. According to the Korean chronicle Dongguk Tonggam, more than 100,000 men of the Yuan army and over 7,000 soldiers of Goryeo failed to return. It is known that while seven tenths of the Goryeo force did make it back, the southern Jiangnan army was almost entirely destroyed.

In a manner substantiating this, nearly all of the vast amount of pottery found at Takashima are items made in the Jiangnan region of China. Also, as it appears that boats lashed by the waves crashed into each other, breaking up and sinking to the bottom of the sea, pieces from multiple ships have been found thus far in the waters off Takashima.

Excavation of a Mongol navy ship

In October 2011, in one corner of the Takashima Kōzaki site, an underwater excavation was conducted in order to shed light on the conditions of the Mongol invasion.

As a result, a keel, which forms the backbone of a ship, was ascertained lying horizontally in an east-west direction near the center of the excavation precinct, with members from the ship’s bottom (the planks) running along both sides in parallel fashion. Large amounts of brick were scattered on top of the keel and the planks, and among the items verified as mixed together with these, there are four-lugged jars and large vases of Chinese manufacture, celadon bowls, inkstones, copper coins, metal semi-spherical and round clay objects.

From the condition confirmed for these finds, the ship’s body and the scatter of artifacts clearly spread beyond the area of this investigation, and accordingly this ship from the Mongol invasion is inferred to be a large-scale example more than 10 m in overall length.

Designation as a Historic Site for clarifying the Mongol army

Investigation of the Takashima underwater site began in 1980, and from the following year a campaign was begun to make an area stretching 7.5 km along the south shore of the island, and extending 200 m out to sea, widely known as a deposit of buried cultural materials. In excavations conducted to date, in addition to anchor stones and wooden members from boats, there are jars and other vessels of celadon, lacquer ware, and swords and armor among the many Mongol invasion artifacts known to be buried, and in March 2012, within the area known for its deposit of buried cultural materials, 384,000 m2 in the vicinity of Kōzakimen on Takashima was designated a Historic Site.

In addition to continuing the investigations through excavation, it is hoped that the structure of the uncovered ship will be reconstructed, and that in addition to its ships the true shape of the Mongol invasion itself will come clearly into light. (Ikeda Yoshifumi)

|

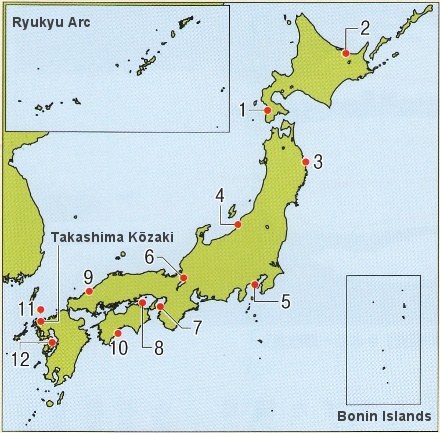

Principal

underwater sites of Japan

|

Column: The Takashima Submerged Site and underwater archaeology

Japan is an island nation surrounded by the sea. The Japanese have long utilized the sea, and rivers and lakes, as places to catch fish for food, or as routes for transporting people and goods.

Due to changes in climate and movements of the earth’s crust, the levels of the sea, rivers, and lakes rise and fall, and submerged sites are formed on lake and sea beds. It is also believed that many ships and their goods, which sank in the water on account of unforeseen conditions, lie buried at the bottoms of lakes and the sea. These are called underwater sites (i.e. at sea, lake, and river bottoms), and the field of archaeology which conducts research and investigation of such sites is called underwater archaeology.

The contents of investigation in underwater archaeology are basically the same as for terrestrial sites, but there are various obstacles and limitations such as water opacity, the strength of tides and currents, the thickness and nature of the deposits at water bottom, and restrictions on diving time due to water depth. Among equipment used in normal investigations for surveying, making visual records, and excavating to begin with, and also among paraphernalia for scale drawing such as paper and drawing boards, there are many items that cannot be employed underwater. In addition to conventional archaeological knowledge and techniques, the skills of using underwater equipment, and moreover the underwater techniques and knowledge for adapting to the aquatic conditions which differ with each site, must be acquired in order to carry out underwater archaeology.

In Japan, underwater archaeological research began in earnest with the investigation, starting in 1974, of the Edo shogunate’s battleship Kaiyōmaru, at Esashi harbor in the Hiyama subprefectural district of Hokkaido. With the conduct of subsequent investigations, such as that of a sunken ship from around the fourteenth century and loaded with Bizen ware, at the Mizunoko Iwa site in the waters off the island of Shōdoshima, interest in underwater sites began to increase. In the midst of these developments, the investigation at the submerged site of Takashima began from 1980. A variety of methods have been tried out in the investigation at Takashima, such as grasping the seabed topography with side-scan sonar and using an airlift pump to remove silt. Improvements in these techniques continue to be made, and as more advances are seen, conditions at such sites under the sea will likely become even clearer in the future. (Ikeda Yoshifumi)

(principal artifacts, Takashima Kōzaki Site)

Iron helmet Kamakura period, ca. 720 years ago. Height: 24.1 cm; weight: 3,560 gm. |

'Phags-pa script seal Kamakura period, ca. 720 years ago. (Stamp plate dimensions) Length of each side: 4.5 cm; thickness: 1.5 cm. Made of bronze. This seal was found on the coast at Kōzaki in 1974. On the back side of the stamp plate is an inscription to the right of the grip, naming a military rank equivalent to a company commander, and another to the left of the grip giving the date of commission as the ninth month of 1277 (see photo at right). 'Phags-pa script was an alphabet which Yuan dynasty founder Kublai Khan ordered the Tibetan Lama Pagba to devise, and was used for official items such as documents and seals. It was used very little after the collapse of the Yuan. |

Bomb Kamakura period, ca. 720 years ago. Diameter: 15 cm. A 4-cm diameter round hole for inserting gunpowder was opened in the top. | |

White porcelain bowl Kamakura period, ca. 720 years ago. Rim diameter: 14.75 cm; height: 7.15 cm. | |

Brown glazed four-lugged vase Kamakura period, ca. 720 years ago. Height: 31.75 cm. The four lugs are not positioned evenly around vase. Shorter items have also been recovered, which resemble this in the vessel shape, the method of attaching the lugs, the outward turn of the rim, the application to the rim of a band with a triangular cross section, etc. |

Male and female deer statue in saphire Kamakura period, ca. 720 years ago. Height: 3.45 cm. This is a finely worked, minute openwork carving, with a male and female deer under a tree on each side. It was used as a decoration for the top of a helmet or crown. |