Scene from the excavation

Excavation in progress of a Final Jōmon obsidian quarry pit, at a depth about 3 m below the ground surface. The obsidian dike has fine fissures running vertically and horizontally, and when impacted fractures into board or columnar shapes. Jōmon people made use of this characteristic to obtain raw material; in order to avoid damaging the dike, the excavation was conducted gingerly while lying on one’s belly. Adapted from Hakkutsu sareta Nihon rettō 2016 [Excavations in the Japanese Archipelago, 2016] (Bunkachō [Agency for Cultural Affairs], ed., Kyodo News, 2016).

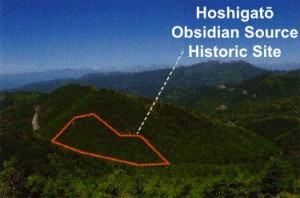

Panoramic view of the site

Adapted from Hakkutsu sareta Nihon rettō 2016 [Excavations in the Japanese Archipelago, 2016] (Bunkachō [Agency for Cultural Affairs], ed., Kyodo News, 2016).

Current condition of an obsidian quarry site

The arrow is at the center of the surface depression of a quarry site.

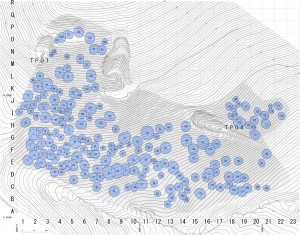

Distribution map of obsidian quarrying pits

Quarrying pits at 193 locations concentrate over an expanse of approximately 35,000 m2.

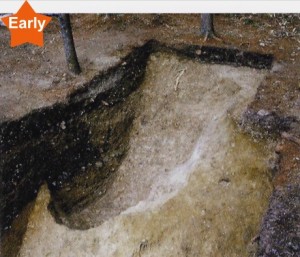

Obsidian quarry pit of the Early Jōmon (approximately 5,700 years before the present)

This was discovered around 1960. Because quarrying of obsidian for insulating material (perlite) was still underway at the time, the upper portion of the quarry pit was cut away, and its scale and shape are thus unclear. Potsherds were recovered from the lower portion, which is large enough for a single adult to enter. Adapted from Hakkutsu sareta Nihon rettō 2016 [Excavations in the Japanese Archipelago, 2016] (Bunkachō [Agency for Cultural Affairs], ed., Kyodo News, 2016).

Traces of quarrying

Long, narrow marks from digging, about 2 cm wide, were left in the wall of the quarry pit. The shape and size match the tip of the first tine of a deer antler (the antler in the photo is a modern specimen). Adapted from Hakkutsu sareta Nihon rettō 2016 [Excavations in the Japanese Archipelago, 2016] (Bunkachō [Agency for Cultural Affairs], ed., Kyodo News, 2016).

Obsidian quarry pit of the Final Jōmon (approximately 3,000 years before the present)

A dike formed on the periphery of the rhyolite bedrock of Mt. Hoshigatō was quarried to a depth of 1 m or more. The obsidian source stones thus obtained were transported to various parts as material for stone points. Adapted from Hakkutsu sareta Nihon rettō 2016 [Excavations in the Japanese Archipelago, 2016] (Bunkachō [Agency for Cultural Affairs], ed., Kyodo News, 2016).

Obsidian quarried by Jōmon people and the tools they used

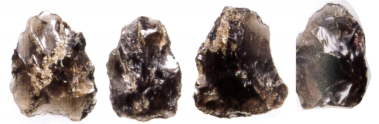

Obsidian raw material

A portion of the source stones recovered from a Late period quarry pit. Lengths are approximately 3–8 cm. The pieces are often split or pointed at one end from the impact of the hammer stone used for quarrying.

Jōmon pottery

Recovered from a Late period quarry pit. The portion extending from from the rim to the body which appears blackened consists of carbonized surface material. It is seen that Jōmon people brought pottery for cooking with them to the quarry site, taking meals as they worked there. Surviving height: 23.5 cm.

Hammer stones

Recovered from a Late period quarry pit. The item at upper left is 8.1 cm long and 4.1 cm wide. Jōmon people chipped out the obsidian dike bit by bit with hammer stones that could fit entirely into the hand.

Unfinished points

Recovered from a Late period quarry pit. These indicate that the quarried obsidian was circulated to various regions after being partially shaped. These are valuable materials linking sites of production and consumption. The item at right is 3.6 cm in length.

Hoshigatō Obsidian Source Historic Site, Shimosuwa Town, Nagano Prefecture

Early, Final Jōmon periods (approximately 5,700 and 3,000 years before the present)

Quarry remains discovered at 193 locations

The Hoshigatō Obsidian Source Historic Site is spread within a forest at 1,500 m elevation on the eastern slope of Mt. Hoshigatō, located in the northwest portion of the Mount Kirigamine massif. This area was identified as an obsidian source site through a survey conducted in 1920 by Torii Ryūzō, and the remains of Jōmon period obsidian quarries were made clear in an investigation conducted from 1959 to 1961 by Fujimori Eiichi and others.

In a distribution survey carried out between 1997 to 2013, it was newly learned that Jōmon period obsidian quarry sites still surviving as only partially filled in surface depressions are found at 193 locations over an expanse of approximately 35,000 m2. Further, as quarry pits from the Early and Final Jōmon periods (approximately 5,700 and 3,000 years ago, respectively) were found, it could be confirmed that the quarrying of obsidian was conducted over a long period of time.

Quarrying methods differing by period

From quarrying pits confirmed in this survey for two different periods, it was learned that completely different methods were employed for quarrying in the Early and Final Jōmon periods. Early period quarry pits were vertical shafts large enough for a single adult, where obsidian lumps included in pyroclastic flow deposits are inferred to have been dug out using a deer antler as a pick. On the other hand, in the Final period it is thought that the obsidian dike itself lying 1.5 m or more below the surface was struck with hammer stones in order to obtain obsidian as source stones. The portion of dike uncovered in the investigation extended over roughly 5 m2, and within this area as many as 12 round or oval quarry holes both large and small were found, from which the concentrated manner of quarrying the dike by people at the time may be discerned. As the yield per cubic meter of quarried material is provisionally calculated as 1,300 kg, it is inferred that several hundred kilograms of obsidian were dug out from a single hole of this type by people of the Final Jōmon period.

It has been made clear from scientific analysis for identifying rock sources that obsidian produced at this site from the Early Jōmon period onward supplied an extremely broad area extending from the Tōhoku to the Tōkai and Hokuriku regions. As background to this large volume of obsidian circulating over a wide area, the current investigation has clarified the quarrying activities carried out at the source. This is a highly significant finding for considerations of the actual conditions of Jōmon period exchange and the structure of society. (Miyasaka Kiyoshi)